Weight follows who we become

Weight control is a byproduct of eating well, not the vehicle to a good way of eating. If we weigh 200 lbs, we eat like someone who’s 200 lbs. If we eat like someone weighing 140 lbs, we’ll lose 60 lbs. We could also lose 60 lbs by eating like a prisoner of the Gulags. The difference is becoming a better person versus merely losing weight. And, if w eat like a prisoner, we have to anticipate a prison break. The purpose of a prison is not harm, but rehabilitation. If we don’t rehabilitate, we’ll revert to our former ways and former weights. The task at hand is to enjoy becoming a person who wants to be well above all else.

We do well to deemphasize weight loss and fixate on our flourishing. This will not be easy. People have been telling us to lose weight for as long as undesired weight gain has been a problem. Remember that weight gain is not the problem nor is weight loss the solution.

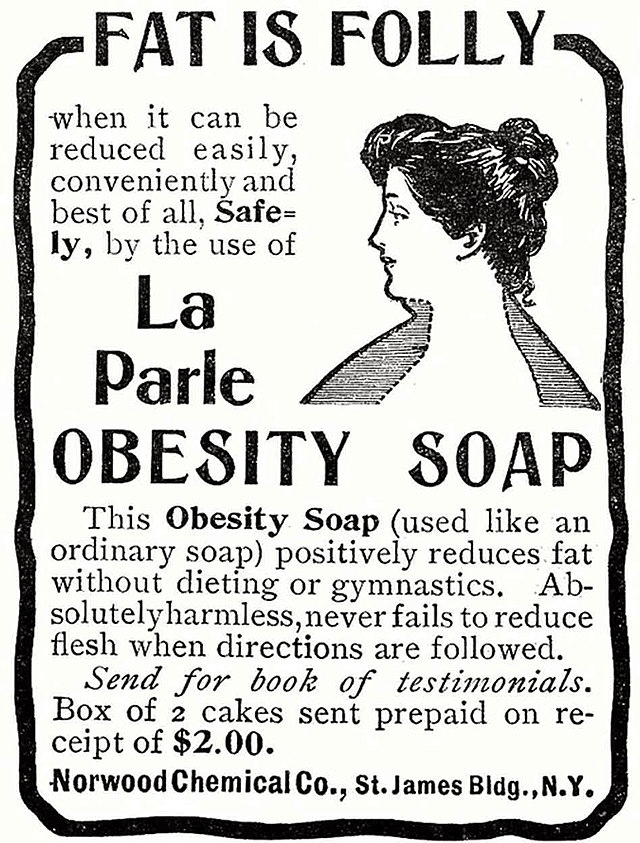

Stores line their checkouts with candy and glossy magazines with callouts like, How I Lost 80 Pounds In 6 Weeks! or 15 Healthy Fat Burning Tips For The New Year or 99 Foods Skinny People Avoid. Weight loss is always made out to be the ultimate goal. And, worse, it’s depicted as a complicated thing, a code to be cracked with some secret knowledge. Hence when someone loses weight, they’re often asked, “what’s your secret?”

Weight loss is governed by well-known laws of physics. It's impossible not to lose weight when the conditions are right. It’s a bodily response to a calorically-restricted environment. It’s not a mystery, we are.

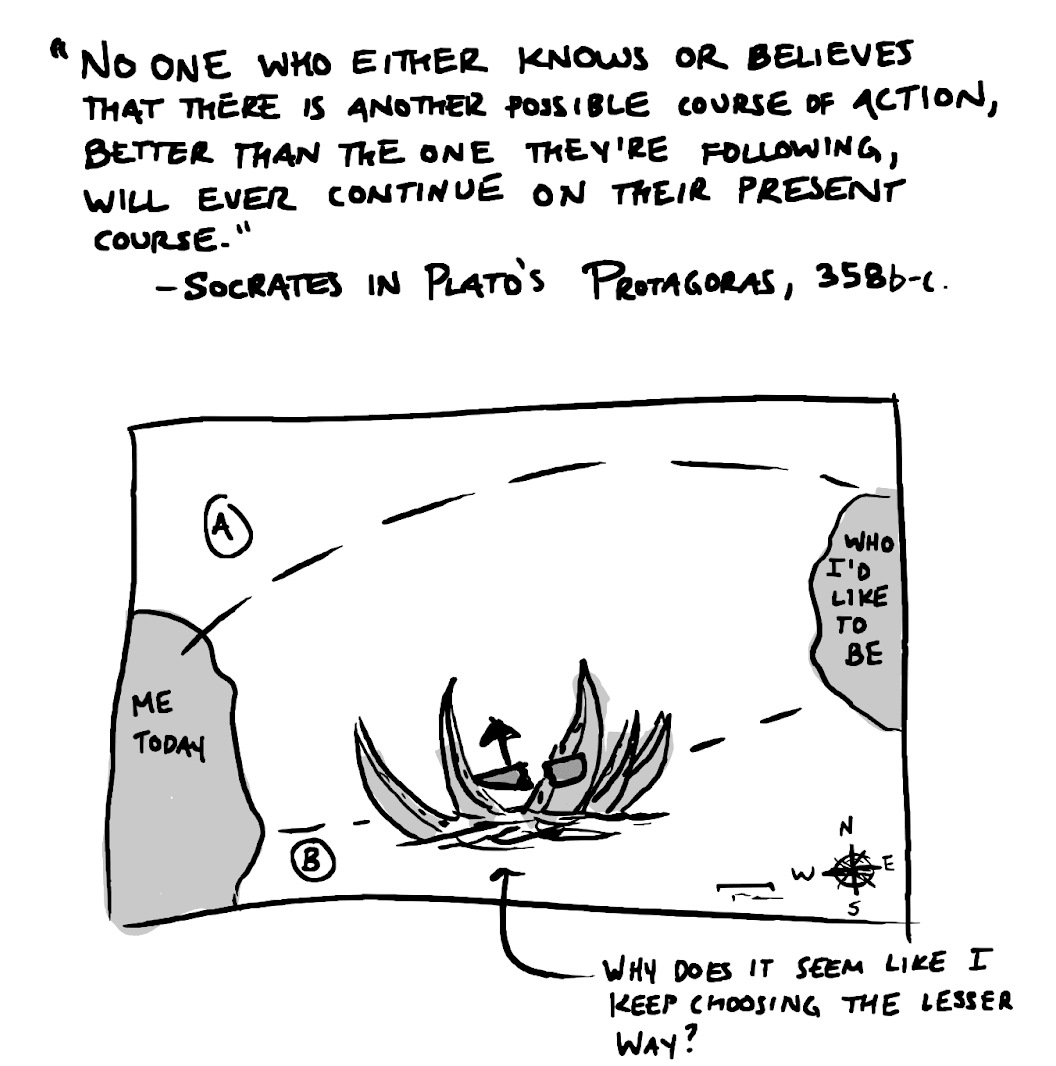

Why would we ever eat in a way that sustains our undesired weight gain?